There is no mistaking the fact that you’re walking into an old administrative building when you visit PINK, ‘a gallery, artist studios and event space dedicated to advancing interdisciplinary research, innovative practice and collaborative exchange’. From the corporate glass entrance and welcome desk to the thin wiry carpet and ceiling tiles, the building is every soulless stereotype of an office block that you could conjure. Then you reach the second floor and it all changes. This is the main exhibition, event, anything-you-want space and central hub of PINK.

The space is bright, with two of its four main walls made up of windows. Amongst the glass and the plethora of radiators and plug sockets that powered the former workspace, there are currently delicate works by visual artists Elaine Grainger and Moa Gustafsson Söndergaard. Their exhibition Echo Mapping is the first in PINK’s new series of international residencies, inviting artists to create site responsive work reflecting on Stockport’s shifting landscape, encouraging fresh perspectives on aspects of the town often overlooked by locals living amongst it. The last few years have brought tangible change to the former industrial town, resulting from a one-billion-pound investment in it from the council to ‘attract individuals and businesses to live, work, play and connect’ by improving transport links, investing in leisure amenities, maintaining historic features and building new business areas, housing opportunities, and creative hubs.

Grainger and Söndergaard have worked on several projects together after meeting in Reykjavik in 2023 and discovering shared interests in architecture, the impermanence of place, local materials, word mapping, movement and the ephemeral. A key mutual process is walking, and this is what they spent much of their time in Stockport doing – observing the intersection of humans and the built environment, the town’s disorientating topography and its industrial past and urban transformation. ‘You can feel its history and see its future’, notes Grainger poetically as we speak on the opening night. ‘You can see the traces and fading and bleaching which is the sort of ephemerality we’re both interested in. A place like this kind of sits in you, you feel it.’

To document this, Grainger and Söndergaard took thousands of photos and interrogated the place and its direction through mind and word mapping within the gallery space which served as an active research hub. They then returned to their homes – in Ireland and Sweden respectively – to work separately, maintaining contact with each other and PINK’s curator/director Katy Morrison via video calls. The week before opening they returned to Stockport to communally install the works, having decided that they would occupy different planes – Grainger the floor and Söndergaard the windows.

Elaine Grainger and Moa Gustafsson Söndergaard, Echo Mapping, PINK 2025, installation view. Image shared courtesy of the artists.

As you enter the space you see Grainger’s ‘Manual of Infinite Movements’ (2025) – small objects covering a large central area of the floor, visually similar to a cross between Sarah Sze’s (born 1969) graceful yet precarious assemblages and Tony Cragg’s (born 1949) readymade flat lays. As you crouch down to decipher what you are looking at, and discern between object and shadow as the sun dances across the window-lined space, familiarities start to come out. There are plastic cable ties and plaster casts of cable ties, marbles, wire, and loosely formed clay shapes still bearing the trace of Grainger’s hand, all laid upon and around a list of words typed and printed onto vinyl.

In Ireland, during the pre-election period candidate posters are displayed across towns using cable ties then cut down during the aftermath. Following the 2024 Irish general election, Grainger noticed hundreds of cable ties adorning the streets where posters had hung, and she began collecting them on her walks to and from her studio – a record of her movements. To her they represented not only ephemerality – a recurring theme in her work – but also the increasing commodification of our attention, where people, brands and campaigns vie for our consideration. Not just to sell products but ideas, causes and politics. This notion of drawing and holding attention is also reflected in Grainger’s use of the floor. ‘It’s often ignored’, she states, but it is where she works in her studio. It therefore seemed a natural choice, also lending itself to what she describes as the ‘playful, performative’ act of placing and moving the components.

Grainger was interested in Stockport’s infrastructural connections – the trains, the viaduct, the river Mersey – and the cable tie became a metaphor for this. The resistors used in train engineering are usually made of ceramics or glass which informed her use of clay and inclusion of glass marbles, while the text work which literally and figuratively underpins the piece lists her research materials and brainstormed words. The marbles link back to the notion of play and act as pops of colour to an otherwise greyscale work, as well as reminding you how beautiful these children’s toy, commonplace throughout the early and mid-twentieth Century, are.

Elaine Grainger and Moa Gustafsson Söndergaard, Echo Mapping, PINK 2025, installation view. Image shared courtesy of the artists.

The other work Grainger produced, ‘Score of Infinite Movements’ (2025), features three flat screen televisions laid on the floor with their wires and cables fully exposed, displaying synchronised footage cutting between images gathered in Stockport, Morocco, Dublin and Japan. The visible electronics give a fluidity to the work, embodying Grainger’s interest in presenting the process rather than the perfected, and aesthetically resemble the sort of map features that so interested the artist – contour lines, roads, railways and rivers. These universal connectors intertwine around the screens showing clips that are harder to assign to their respective country than you might expect, and the wires pull these places together into a physical embodiment of Grainger’s experiences and consciousness.

Aesthetically, Söndergaard’s works chime so neatly with Grainger’s ‘Manual of Infinite Movements’ that you could be excused for thinking they were made by the same artist. Her ‘Blueprint’ series (2025) consists of four works of vastly differing sizes made using second-hand fabric painted with beeswax. The wax turns the fabric translucent whilst the threads laid over the surface creates a subtle pattern – the weft is structured, evenly spaced and straight, whilst the warp is meandering and wild. The resulting loose grids represent Stockport’s changing layout whilst the wandering line recalls its paths, waterways and roaming elevation.

Applying beeswax to the fabric was a new technique for Söndergaard who is drawn to experimentation and chaos, though these works are gentle and refined. ‘In the Western world, order is seen as good and chaos as bad’, she tells me, ‘but in indigenous communities that isn’t the case’. So, instead of eschewing chaos, Söndergaard embraces it, learns from it and runs with it. She likens this to Stockport’s skyline – jarring, wonky, mismatched – and the attitude of the locals ‘adapting and embracing the change’. This dynamism is reflected in how Söndergaard eventually installed the works. They are all hung differently – one draped and shifting in the light breeze, one tightly framed and propped on a windowsill. Another is in front of a window revealing traces of movement outside, and one is mounted on a column that blocks light to the middle of the work. They allow the building and town to affect the work even after its completion.

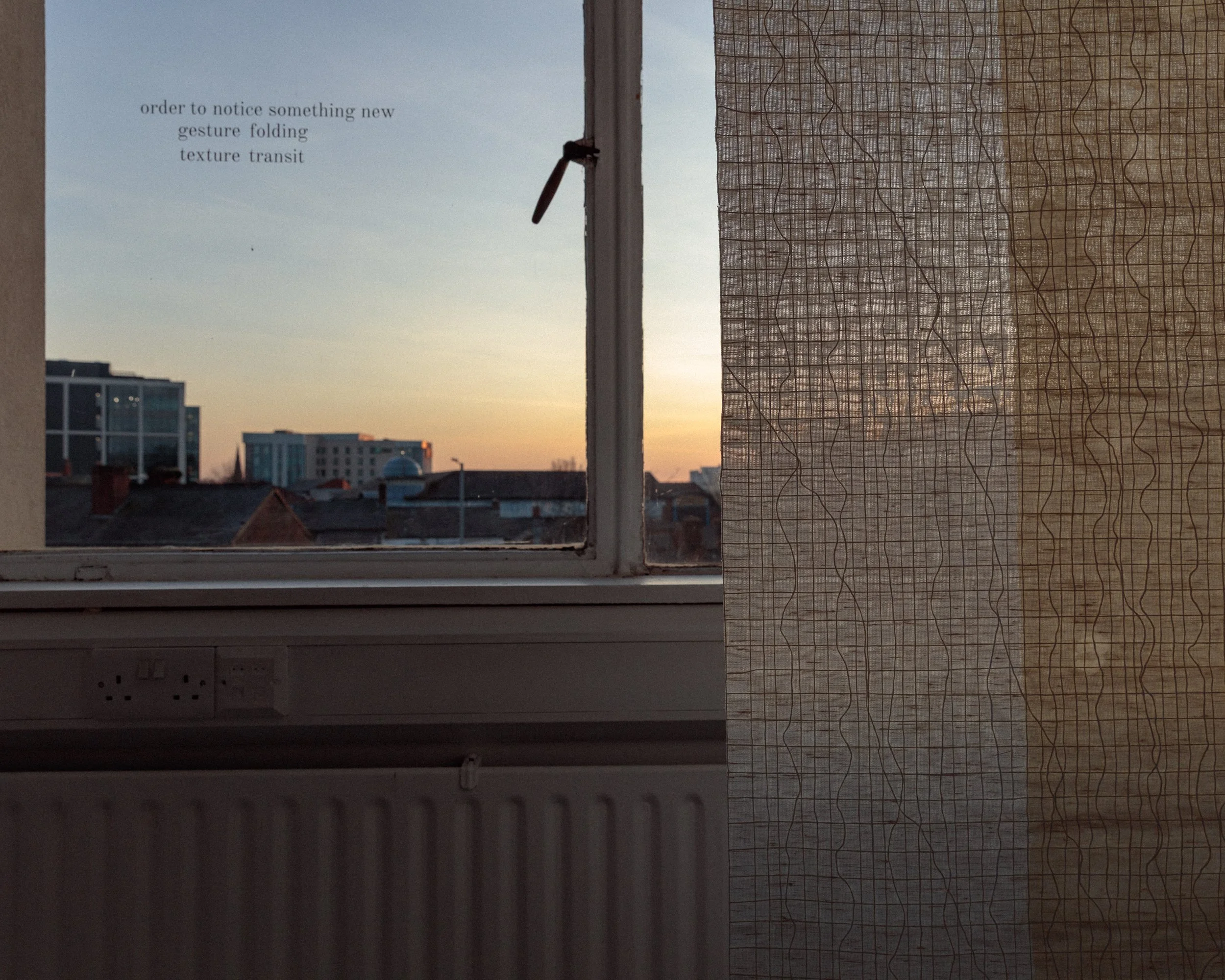

This theme of working with the unusual space, rather than fighting against it, continues with Söndergaard’s other work, ‘Bird, Fish or In Between’ (2025) where lines of vinyl text have been adhered to the expansive windows that line the exhibition space, containing it yet opening it to the outside world. There are twelve stanzas positioned at different levels. Each comprises three short lines, the structure of which comes from a traditional Swedish game ‘Hide the Key’ where seekers locate the hidden key by asking the hider if it is a bird (high), a fish (low) or in between. The words themselves are poetic suggestions, partial thoughts, a fleeting sense of something not captured but offered up to be pondered over. Similarly to Grainger, Söndergaard rarely works with bold colours but wanted to introduce a subtle palette of yellow, orange and red that mimicked the sun’s rise and fall through the windows behind.

Elaine Grainger and Moa Gustafsson Söndergaard, Echo Mapping, PINK 2025, installation view. Image shared courtesy of the artists.

The work is influenced by Söndergaard’s research into what it means to be human in a world in flux, one where we are replacing connection with the natural world with the digital one. This inability to ground oneself and take stock of your place in time and space was galvanised by Stockport’s layered architecture and undulating landscape which makes locating ground level challenging. The text’s format and placement make it difficult to see at first, conjuring that feeling of disorientation. To remedy this, you have to move closer, negotiate the light and search like you’re playing your own game as the words slowly reveal themselves as both you and they settle into the space.